What is a pingo, and why should we care to know?

In the last week of February, 2015, after more craters had been found, a compelling clue emerged as to the cause of the Siberian craters. As reported by The Siberian Times, once other craters started appearing or being identified (at least 20, possibly dozens), scientists had a sample large enough for meaningful comparison with older satellite images.

A pingo once existed at each crater site.

The disappearance of a pingo from each crater site indicated certainty of pingo involvement in the crater formation.

A pingo is a hill formed around an upheaving ice core.

Pingos are found not only in the earth’s polar regions, but also in Earth’s high-altitude regions such as the Alps and the Himalayas, in connection with permafrost.

Pingos, along with the permafrost active (top) layer, will seasonally degrade and melt, and re-freeze. In some regions, such as the eastern tip [Fig. 6] of the wider prong of the Yamal Peninsula, this process creates fissures in the surface of the landscape where ice wedges grow to be quite large. The ice-wedging process creates permafrost patterning, easily visible from a satellite image.

A melting pingo and polygon wedge ice near Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada..

Image attribution: By Emma Pike [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Pingos are useful markers of a permafrost landscape.

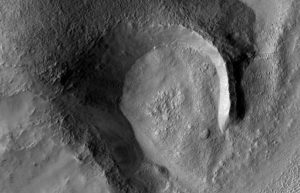

Because of the limited conditions under which pingos and permafrost form, and because permafrost conditions can develop patterning from seasonal thawing and re-freezing, scientists have sought to explain similar formations in the solar system by their Earth analog forms. While patterns may develop on terrains in warmer regions, the presence of pingos identifies a permafrost landscape. NASA has identified possible pingos on Mars.

Possible pingo in Mars Protonilus Mensae region, imaged in April, 2015, by NASA. Source: NASA via High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, University of Arizona.

Relicts of collapsed pingos provide keys to geologic and atmospheric history.

Because a pingo’s core is made of ice, a pingo can collapse with warming, leaving behind a circular depression, such as in the image above.

In the United Kingdom, collapsed pingos from the Devensian Ice Age are being identified, mapped, and designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest, by citizens and scientists working to preserve the natural environment.

Small collapsed pingo relict, one of many on Thompson Common, Norfolk County, United Kingdom. Attribution: Hugh Venables, August 2007 [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Small collapsed pingo relict, one of many on Thompson Common, Norfolk County, United Kingdom. Attribution: Hugh Venables, August 2007 [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

To briefly see the mechanics of how a pingo will form and collapse, visit the next page.