The angled femur of Lucy’s knee confirmed she walked upright, like humans.

Image: Australopithecus afarensis knee from Hadar (AL 129-1). Found in 1973 by Donald C. Johanson

Image Attribution: By Chartep (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

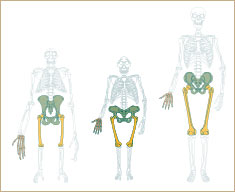

Bipedalism requires an angled femur for more comfort.

This image shows examples of the hypothesised small shifts required to turn a quadraped into a biped. Tiny changes in the angle that the femur enters the pelvis allow bipedal walking to be more comfortable. Image: from “The Complete World of Human Evolution,” 2005, ISBN 978-0500051320, Authors: Chris Stringer, Peter Adams.

How was Lucy discovered in Ethiopia?

Discovering Lucy was a turning point in the study of the hominid family tree. Twenty years later, Ardi would prove an equal challenge to former theories about early hominids. Here’s a summary of the trail followed to make these significant finds in Ethiopia.

While hunting for fossils in Ethiopia’s Afar Triangle on November 24, 1974, paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson and graduate student Tom Gray stumbled upon the partial remains of a previously unknown species of ape-like hominid. Nicknamed “Lucy,” the mysterious skeleton was eventually classified as a 3.2 million-year-old “Australopithecus afarensis”—one of humankind’s earliest ancestors. The headline-grabbing find filled in crucial gaps in the human family tree, but it also shook up ideas about early human evolution and upright walking. Forty years later, learn the story behind the fossil that permanently changed scientists’ understanding of human origins.

Dr. Donald Johanson woke up on the morning of November 24, 1974, feeling lucky. The paleoanthropologist—then a professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland—was several weeks into his third expedition to Hadar, Ethiopia, a site that had proven to be a treasure trove of early fossil remains. His international field team had already found leg bones and several jaws that were among the oldest examples of hominids—the family of bipedal primates that includes humans and their ancestors—and Johanson was convinced that an even bigger discovery was in the offing. When an American graduate student named Tom Gray announced he was leaving to scout out a nearby fossil site, Johanson had a hunch he should tag along. “I felt a strong subconscious urge to go with Tom,” he later wrote. “I felt it was one of those days…when something terrific might happen.” Ignoring the already scorching heat and the mountain of paperwork on his worktable, Johanson hopped in a Land Rover with Gray and made the four-mile journey to a gully on an ancient, dried out lakebed. Before he left, he made a brief note in his journal: “To Locality 162 with Gray in AM. Feel good.”

Johanson and Gray’s search turned up very little at first. The pair found a few animal bones and teeth, but nothing extraordinary. After a few hours of scouring the sunbaked ground, they decided to take a detour through a nearby gully for one last look. There, Johanson spotted what he instantly recognized as a piece of hominid elbow bone protruding from the dirt. When he and Gray bent down to examine it, they saw that it rested next to other pieces of thighbone, vertebrae and ribs. All appeared to belong to the same skeleton. “We were just astounded,” Johanson later told the New York Times. “You just don’t expect to find this much of a single individual.” Johanson and Gray raced to tell their colleagues. As they drove up to their camp, Gray laid on the horn and yelled out, “We’ve got it! Oh, Jesus, we’ve got it. We’ve got the whole thing!”

That night, the jubilant field team celebrated the discovery over dinner and several cans of beer. In the background, a stereo blared with The Beatles’ album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” on repeat. When the song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” came on, someone suggested calling the new skeleton “Lucy.” The name stuck.

Along with the expedition’s co-director, the French geologist Maurice Taieb, Johanson and the rest of the field team spent the next several days scouring the Lucy discovery site. They found dozens of intact pieces of leg, pelvis, hand and arm bones as well as a lower jawbone, teeth and part of the skull. All told, the pieces amounted to about 40 percent of what appeared to be at least a three million-year-old hominid skeleton. A more ancient or complete specimen had never been discovered.

To read the details of what the scientists found, and how Lucy and Ardi are placed on the hominid family tree, read the source article here: History.com