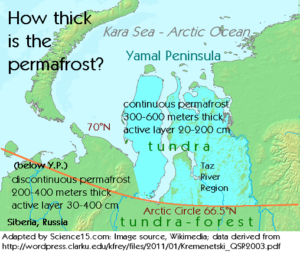

Depth of permafrost on the Yamal Peninsula

Depth of permafrost on the Yamal Peninsula

Source: Map adapted by Science 15; data derived from this article, geography section.

What does a landscape tell us about permafrost?

If you see both tundra and pingos, you are likely above 64° of latitude, in an area of continuous permafrost.

Videos of the Yamal craters, on preceding pages, have shown the Yamal Peninsula tundra. The entire Yamal Peninsula is inside the Arctic Circle and is underlain by continuous permafrost. Here is another view of the terrain.

Some of the pictures of the Yamal Peninsula terrain from prior pages of this article are included in the video above. In summary, the continuous permafrost zone, largely above the Arctic Circle, is an area of flat tundra dotted by pingo (ice-core) hill formations and “thermokarst” lakes (formed from melted ice wedges).

If you see both tundra and “tundra-forest,” known as “taiga,” you are likely between 64° and 60° of latitude, in an area of discontinuous permafrost.

In areas surrounding the Yamal Peninsula, bordering the Arctic Ocean but about 2.5 degrees of latitude below the Arctic Circle (which is at 66.5°N latitude), areas of tundra mix with forest lands called taiga. Taiga lands have different depths of permafrost.

Continuous permafrost extends southward from the Arctic coast to approximately 64°N latitude (Fig. 2). . . . Discontinuous permafrost is found [from about 64°N latitude] to about 60°N latitude, with sporadic permafrost occurring south of that.

Source: Kremenetski article.

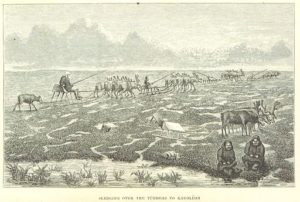

Tundra and taiga appear side by side in a discontinuous permafrost region.

Here is an 1875 drawing depicting travelers heading across tundra, with taiga in the distance. They are headed for the Karelian region of Russia, which borders Finland at the White Sea, Arctic Ocean, and forms the northwestern extent of Siberia, Russia.

Sledging over the Tundras to Karoleon Russia.

Source: 1875 Image extracted from page 008 of The Land of the North Wind; or, travels among the Laplanders and the Samoyedes, by RAE, Edward – F.R.G.S. Original held and digitised by the British Library. From Wikimedia, as copied from Flickr.

The image below is a Larix gmelinii (larch) forest, or taiga, at the northwestern corner of Sibera, in the Kolmya River region. Pingo relicts, from colder times, may be found in such areas. Could the mountain to the right in this image be an uncollapsed pingo? Consider that a larch will grow to 98 feet and a pingo may grow to 218 feet with a 2,000-foot diameter. It’s fun to speculate, but the answer is unknown.

Tipping larches reflect melting permafrost.

The below image is of a more lush forest, situated between the Yamal and Taymyr Peninsulas, at .5 degrees of latitude below the Arctic Circle, but still in an area of possibly continuous permafrost.

Larch forest where permafrost melt has dislodged roots.

Larch forest where permafrost melt has dislodged roots.

Larix gmelinii forest. Kochechum River, Evenkiyskiy Avtonomnyy Okrug, Russia; 66°20’N 99°00’E.

As we traveled down river, I saw what the Siberians call a “drunken forest”. This area is permafrost, where the soil stays firmly frozen year round. Larch grows well here, but their roots are shallow. When permafrost melts, the trees lose their footing and tilt to the side. I guess the trees look like a drunk trying to walk home, tilted at crazy angles. It is a curious sight, but it is also a clear sign that the temperature in that spot has been warm enough to melt the permafrost.

Image Attribution: By Jon Ranson, NASA Science blog (NASA Science blog) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s clear the active permafrost layer may be melting due to Arctic warming. But what is happening underground?

To see how geologic processes may be warming permafrost from below, visit the next page.